Article

7 August 2024

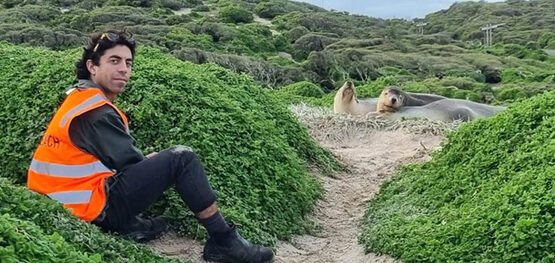

This article by hub researcher Nathan Angelakis is republished from The Conversation.

Across the world’s oceans, our knowledge of the seafloor is very limited. Mapping and studying deep, remote offshore areas is difficult, expensive and time-consuming. So much of the ocean has not yet been explored.

But what if marine mammals could help? In our new research, my colleagues and I attached underwater cameras and trackers to eight Australian sea lions (Neophoca cinerea) from two colonies in South Australia. The sea lions explored unmapped areas of the ocean, found new reefs, and revealed amazing diverse habitats on the seafloor.

This turned out to be a very effective way to map large areas. That’s because we could use the information to predict habitats in areas the sea lions didn’t visit. These predictive computer models could also be used to assess how the various habitats might correspond to different environmental conditions.

Improving our understanding of how seafloor habitats function, and how human activity may change them, will be crucial if we are to protect these vital ecosystems in the future.

Using sea lions as data collectors

We attached cameras and trackers to eight adult female sea lions – four from Olive Island on the western Eyre Peninsula and four from Seal Bay on Kangaroo Island – between December 2022 and August 2023.

Small, lightweight cameras and satellite-linked GPS loggers were glued to small pieces of neoprene (wetsuit material), which were then glued to the fur of the sea lions.

The equipment weighed less than 1% of the sea lions’ body weight and didn’t stick out very far, so as to minimise drag and allow unrestricted movement.

In each case the equipment was removed after one trip to sea (about 2–6 days), when the animal returned to land to nurse her pup. The data was then collected and downloaded.

Building predictive computer models from the data required several steps.

First, we analysed the video (89 hours in total). We used a computer program, with which we categorised the different seafloor habitats the sea lions visited.

We then time-matched these videos to movement data from our trackers. This ensured we mapped the habitats to the right locations.

Next, we combined this habitat data with environmental data such as nutrient concentrations, sea surface temperatures and seafloor depths. This allowed us to characterise the different habitats the sea lions visited. We could then use this information to predict habitats in areas the sea lions didn’t visit while they were out at sea.

Altogether we mapped habitat across more than 5,000 square kilometres of the seafloor, which until now has never been explored.

What we discovered

Our study shows Australian sea lions use a variety of habitats on the seafloor. These include lush kelp (macroalgae) reefs and meadows, vast bare sand plains, dense sponge gardens and diverse invertebrate reef habitats.

Using machine-learning (a form of artificial intelligence), our models predict these diverse habitats cover large areas of the continental shelf across southern Australia. This machine-learning approach produced really accurate models.

Our models suggest nutrient supply, sea surface temperature and depth are particularly crucial to the distribution and structure of seafloor habitats.

Why our research matters

Through this research we have been able to efficiently map seabed habitats across large, previously unexplored areas of the ocean. This has given us crucial insight into how different conditions may drive the location and structure of seabed habitats.

Using sea lions to map the seafloor has considerable advantages. Sea lions can cover large areas in short time frames, and can access habitats we can’t. This research can also be conducted from land, with fewer people, at relatively low cost compared with traditional vessel surveys.

Furthermore, Australian sea lions are endangered. Their populations across South and Western Australia have declined by more than 60% over the past 40 years.

Our study helped identify habitats and areas of importance to sea lions. This information will be crucial for conserving and managing their populations into the future. Habitats and areas that are valuable to Australian sea lions may also be important to other key marine species as well.

Sea lion cameras also offer a unique way to understand the importance of different marine environments from the perspective of a predator. Traditionally, the quality and importance of different marine environments has been evaluated from an anthropocentric (human-based) perspective.

So this study highlights an important progression in marine science. Using video from a predator like the Australian sea lion is another way we can assess the importance of different marine environments. In future, this approach will help improve our understanding of the world’s oceans and the species that use them.

Nathan Angelakis is a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) – Aquatic Sciences. This project was supported with funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program Marine and Coastal Hub, and The Ecological Society of Australia under the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.