Article

10 June 2025

Sea snake numbers are falling in northern Australian waters. Two species are already Critically Endangered, and many others face growing threats. Accidental capture in fisheries, known as bycatch, is a major concern. More information is needed about how often this happens and which species are caught.

This need is being addressed in Western Australia’s Shark Bay and Exmouth Gulf fisheries. Researchers and commercial fisheries have teamed up in a project funded by the Marine and Coastal Hub to improve sea snake bycatch reporting.

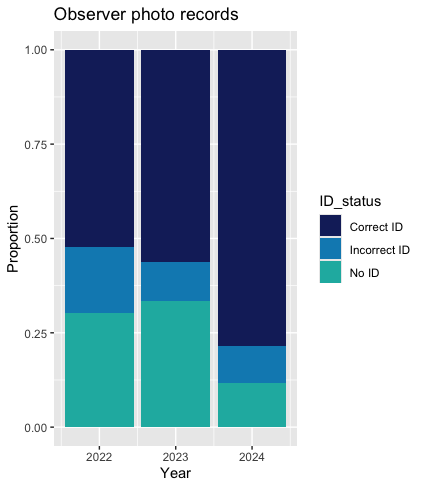

The project is achieving impressive results. Since 2022, the rate of photo-verified sea snake records in Shark Bay has increased fourfold. Successful species identification rates have jumped from 50% to as high as 90% on some boats. Before this project, most sea snakes caught were not identified at all and just recorded as sea snakes.

The project is a partnership between Associate Professor Kate Sanders and Dr James Nankivell from the University of Adelaide, Dr Vinay Udyawer from Sharks Pacific, Dr Jason How from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), and industry partner Sea Harvest Pty Ltd.

“Working closely with government and industry partners has allowed us much greater understanding of the sea snake faunas in Shark Bay and Exmouth Gulf, as well as their genetic connectivity,” Dr James Nankivell of the University of Adelaide says. “Collecting data at a species level is far more valuable than undifferentiated records, as different species may face different threats and require different management priorities.”

To date, researchers have spent 56 days at sea and run three workshops with fishers. These workshops taught fishers how to identify species, safely handle snakes, and collect tissue samples. Some crews now photo-verify every sea snake captured and will continue this work in the 2025 season. For the reporting side, the team is working together with DPIRD to ensure that logbook reporting captures species information.

Supporting fishery sustainability

The improvements are helping more than science. Sea Harvest is using the new data to support Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) recertification in 2026. Reliable reporting will help demonstrate sustainable practices and protect the fishery’s future.

“This type of collaboration with the university, DPIRD and other stakeholders not only strengthens our understanding of sea snake populations and their interactions with fisheries but also enhances the integrity of our reporting systems and our commitment to sustainability,” Johann Botha, Prawn Operations Manager at Sea Harvest, says.

“The findings have direct implications for management decisions and support important initiatives such as MSC certification, which is critical to the Exmouth Gulf and Shark Bay fisheries and our markets. We are proud to be involved in work that is producing real, measurable outcomes for both marine conservation and the long-term viability of our fisheries. Continued collaboration of this kind is essential as we strive for best-practice environmental stewardship while supporting a thriving, sustainable seafood industry.”

While the project focuses on Shark Bay and Exmouth Gulf, the resources and methods produced should be transferable to other smaller prawn fisheries in Western Australia.

Insights on sea snake size and connectivity

The project is also revealing new insights about the sea snake populations. Analysis of snake length has revealed that most caught sea snakes are above the size of sexual maturity. Population genetic analyses have shown that Exmouth Gulf Sea snake populations are broadly connected to those across the North-western Shelf and have low overlap with trawl fisheries. In contrast, Shark Bay populations across four species are relatively isolated and have a much greater proportion of their range overlapping with prawn trawl fisheries.

This project's insights will help shape future management decisions. Accurate, species-level data highlights which populations may need the most protection. Better reporting means better conservation, more sustainable and safer fishing practices, and healthier marine ecosystems. This project is a good example of what can be achieved when industry, government, and researchers work together for a common goal.