Profile

26 September 2024

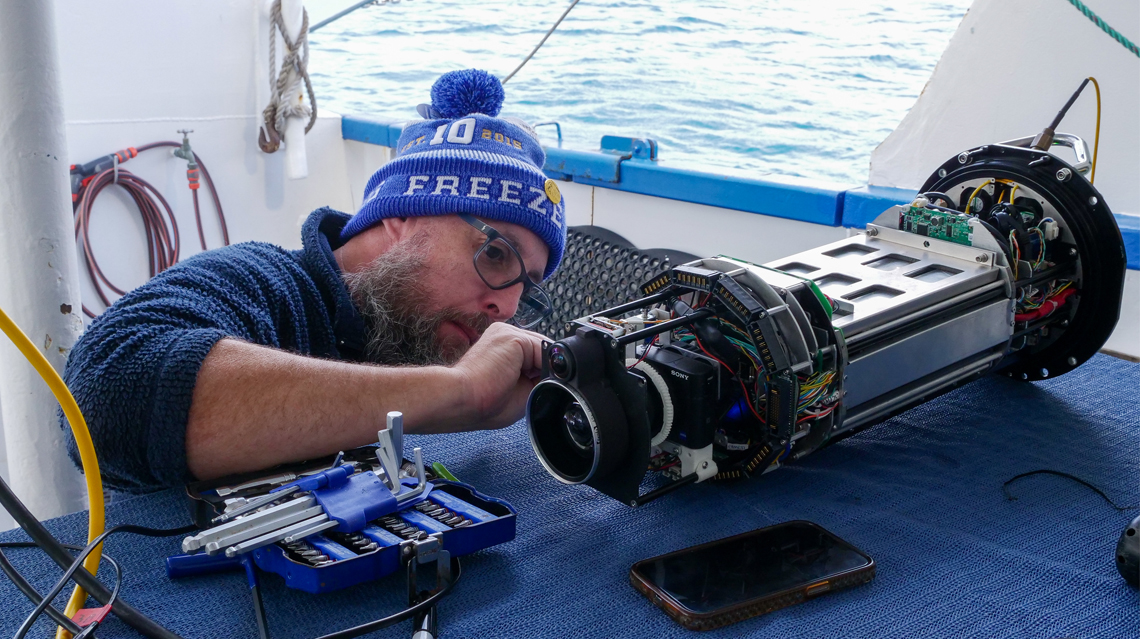

Capturing imagery of amazing creatures at the bottom of the sea is both a job and a passion for this master pilot of underwater robots. Jess Serna Sierra talked to Justin Hulls while onboard the MRV Ngerin during the Beagle Marine Park monitoring survey.

Every school holiday, Justin Hulls’ parents used to take him and his brother to Port Fairy. He learnt to walk in a tent and on that beach on Victoria’s western coast he also fell in love with the sea.

“I knew I wanted to work in or around the water,” he says. That idea led him to study aquatic science at Deakin University, majoring in chemistry.

‘Spud’, as his colleagues call him, started working at the University of Tasmania (UTAS) Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) almost 19 years ago. An early challenge based on trial and error involved learning how to use the first remotely operated vehicle (ROV) brought to UTAS.

Throughout his career, Justin has seen the evolution of this technology. In 2018, he joined the first voyage to survey Beagle Marine Park, funded by the Marine Biodiversity Hub (a forerunner of the Marine and Coastal Hub).

On that pioneering voyage, researchers from IMAS, Geoscience Australia and the University of Sydney Australian Centre for Field Robotics surveyed the submerged Bassian Plain, adding detail to formerly hazy maps of the seafloor.

High-resolution acoustic mapping, sediment sampling and underwater imagery provided baseline information about the shape and structure of the seafloor, its habitats, and invertebrate and fish communities.

Justin deployed baited remote underwater stereo-video (stereo BRUV) systems, which consist of two cameras mounted horizontally and a bait bag in front to attract the fish. The University of Sydney team deployed the Integrated Marine Observing System autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) ‘Sirius’ which follows a pre-programmed path across the seafloor.

In August this year, Justin and his team returned to Beagle Marine Park on the first formal monitoring survey conducted in an Australian Marine Park. This time, he piloted a ‘Boxfish’ remotely operated vehicle (ROV) built in New Zealand. The Boxfish has seven cameras, and Justin can control its path across the seafloor from the vessel in real-time.

“Underwater robots can do what divers cannot,” Jusin says. “In the past we could do two or three dives a day with a team of four divers at 10-metre depths. With this ROV we can do up to 14 transects a day and go to depths of 300 metres.”

Same way every time

So far Justin has worked on surveys in eight of the 60 Australian Marine Parks (AMPs). The list includes the Freycinet, Huon, Beagle, Tasman Fracture, Flinders, Boags, Murray and Lord Howe AMPs. His job has been crucial not only for his team, but for park managers and other researchers.

Since 2020 this has involved using national standard operating procedures developed in a Marine Biodiversity Hub funded project (which continue to evolve under the Marine and Coastal Hub). These standards are contained in the Field Manuals for Marine Sampling to monitor Australian Waters.

Researchers and managers need national standards to collect and process data in a way that allows meaningful comparisons between surveys conducted at different places and times. For example, the standards are essential for Parks Australia to monitor changes in AMPs and make decisions relevant to park management.

Three of the standard operating procedures were followed in the Beagle Marine Park monitoring survey. The first one is about spatially balanced sampling design, which means the survey is not biased to a particular habitat or region and enables robust estimates of the condition of the park. The second is the ROV standard operating procedure which specifies how to deploy the underwater robot.

“For example, this standard specifies a minimum transect length of 200 metres and having a USBL (Ultrashort Base Line) positioning,” Justin says. “This helps to standardise the sampling effort and ensures that the ROV imagery can be precisely located within the park to allow repeat sampling through time.”

Following those transects can be tricky, especially when the currents are strong. A team effort is required, with the vessel’s skipper is key to succeeding in this task.

Justin has lost count of how many voyages he has been on, but certainly not the memories. One of his favorites was a trip to Antarctica, where he went as part of his Diploma in Marine and Antarctic Science.

“As sea ice forms, it traps salt water and algae grows in it,” he says. “When it melts, the krill follows the retreating ice and then other animals such as whales feed on them. My role involved taking cores of ice and passing them through a chlorophyll analysis to evaluate the biomass concentration of sea ice algae.”

While driving ROVs, Justin lets himself enjoy and be surprised by what appears on the screens. For him, driving these robots is like playing a video game, except that: “if you die in a video game, you respawn but if you die with an ROV, you're over… it’s trying to play without dying.”

So far, he hasn’t lost any of his ROVs, so he is Invictus and ready for more adventures.

Acknowledgement

The research voyage on the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) research vessel, the MRV Ngerin, was led by the University of Tasmania Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies. It was supported by the Australian Government under the National Environmental Science Program and a grant of sea time onboard the Southern Coastal Research Vessel Fleet, funded by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.